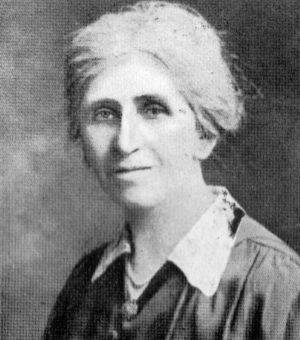

Matilda Knowles

1864 – 1933

Matilda Cullen Knowles, one of the world’s great lichen experts of the 20th century, was honoured in August 2014 with a new commemorative plaque. Born 150 years ago in 1864, Knowles discovered several species of lichens new to science, and was the first to realise that lichens by the seashore grow in distinct tidal zones. At right at the unveiling (left to right) Brian Smyth, Éanna ní Lamhna, Matthew Jebb, Caitriona Lambert and Dr. Marion Palmer.

Knowles worked for 30 years in Ireland’s National Herbarium – then at the National Museum in Dublin. For the last decade of her life, she was curator in all but name – given only the lowly job title of “assistant”. The new plaque at last commemorating her life and legacy, is appropriately at the herbarium, now located at the National Botanic Gardens in Glasnevin, and was unveiled today by botanist and broadcaster Éanna ní Lamhna.

Matilda Knowles was one of Ireland’s foremost botanists, according to the Director of the National Botanic Gardens, Dr Matthew Jebb. “She collected and studied and managed the herbarium, and was effectively the curator, which was very unusual for a woman at the time, and a testament to her skill and knowledge as a botanist.” Knowles began studying the lichens of Ireland around 1909, encouraged by the great Irish naturalist Robert Lloyd Praeger. She went on to become the acknowledged expert on Irish lichens, and in 1929 published the definitive guide to Irish lichens, a 255-page catalogue of over 800 species, including some 100 ‘new to Ireland’ and several species that were ‘new to science’ which she had discovered. It was while studying the lichens of Howth that she discovered how lichens by the shore grow in distinct tidal zones, that can be distinguished by their colour: black, orange and grey.

The new plaque is the latest in a series organised by WITS (the Women in Technology and Science network) and the National Committee for Science and Engineering Commemorative Plaques (NCSECP). Dr Marion Palmer, WITS chairperson, said “it is so important to acknowledge the critical role played by women such as Matilda Knowles. So often their work went unnoticed and unacknowledged at the time, it’s right that we honour them now.” The chair of the NCSECP, Dr Norman McMillan, said that the committee is “delighted to celebrate this extraordinary woman in the 150th year of her birth, and at the herbarium, which she played such a key part in creating”.

Matilda Knowles was born in Ballymena in 1864, moving to Dublin around 1900. She began work in the National Museum around 1903, and was eventually appointed to the position of “non-pensionable assistant”. From 1923 until her death in 1933 she was effectively the curator of the herbarium. Knowles died of pneumonia shortly before she was due to retire, and is buried in Deansgrange.

Mary J. P. (Maura) Scannell

18 March 1924 – 1 November 2011

Always immaculately turned out, a fount of knowledge and a remarkable conversationalist, Maura Scannell has been a central figure in Ireland’s botanical world for over 60 years. A skilled horsewoman in her youth, Maura graduated from University College Cork and became Assistant Keeper of the Natural History Division of the National Museum in 1949. It was there that she developed her deep and thorough understanding of the cultural importance of plants in Irish culture and history.

Maura took a special interest in the botanical details of our past, identifying the various woods of all the Irish harps in the National Museum as well as numerous artefacts from Wood Quay as just two small examples. Her knowledge of charcoal, seeds, fibres and dye plants as well as microscopic algae and fungi and such esoteric subjects as ‘algal paper’ made her an inspiration to generations of botanists. To both young and old, Maura was supremely generous with her time and energy, and a tireless correspondent. She was never too busy to be diverted by an interested schoolboy or schoolgirl visiting the museum, and had a long association, as a respected judge since the 1960s, of the annual Irish Young Scientists Exhibition.

Many of todays leading Irish botanists owe their love of botany to the remarkable adult who took the time to impart her enthusiasm for the plant world. Her fostering of scientists was shared with all, and she assisted Evelyn Booth, then at the age of 82, to collate hundreds of records and to publish the Flora of County Carlow in 1979.

In 1970 she oversaw the transfer of the National Herbarium from the National Museum to the National Botanic Gardens, beginning a 20 year re-establishment of science at the Gardens. Last minute arrangements nearly resulted in major collections being disbursed, until Maura ensured they were moved in their entirety to the National Botanic Gardens. The nursery staff at Glasnevin were well used to her returning on a Monday morning with living plants to be grown on. Through careful studies of living plants she was able to make full use of the gardens as a centre for taxonomic understanding. A singular example was her dogged determination to resolve the identity of the ‘Renvyle Hydrilla’. Leading taxonomists in Britain had identified this plant as an Elodea, but when Maura finally flowered the plant in the Garden greenhouses she was able to prove that the plant was, as she had always suspected, Hydrilla verticillata. Her great interest in history and books gave her the foresight to enable the Herbarium to acquire one of its more remarkable treasures – a bound collection of specimens dating from the 1690s and once owned by Thomas Molyneaux, a founder of the Dublin Society – this was bought from the library at Moore Abbey, in Monasterevin. Her other hunch, to purchase the only known portrait of one the Garden’s founders – Walter Wade – was sadly ignored by the authorities at the time.

On her retirement in 1989 as Head of the National Herbarium, Maura Scannell had already established a remarkable body of work. Her collections in the herbarium are among the largest by any single botanist; all the more remarkable when one considers that most were obtained during her own leisure time. Since retiring she remained an active visitor to the herbarium, a field botanist and author, contributing specimens, answering queries and publishing papers.

The sum of her many specimens, publications and manuscripts represent a vast repository of knowledge about the plants that fill our landscape. Her dedication and assistance meant that she contributed more to the published work of others than to her own, through her thorough attention to correspondence, identification of samples and her intimate and eclectic knowledge of Irish history, geography, ethnography, zoology, geology and botany. From 1963 to 1994 she had remained a constant and active member of the Irish regional committee of the Botanical Society of the British Isles, and in 1995 she was made an Honorary Member of the society.

Maura was presented with the National Botanic Gardens Medal in May 2008, in acknowledgment of her truly remarkable contributions to Irish botany. At the presentation she gave a spirited talk about her delight in the scale of botany, from the microscopic fungi she had discovered, new to science, in the grounds of the Botanic Gardens (Dothiorella davidiae on the fruits of Davidia involucrata in 1976), to exploring for plants in the west of Ireland. She described how it is the little things that are sometimes important, and botanists should record all that they see in a scientific manner, and that no information should ever be overlooked.

Maura produced over 200 scientific publications as well as several important floras and catalogues, besides her thousands of specimens and 10s of thousands of field observations she has left a thorough record of her correspondence in the National Herbarium. In the last year Maura has meticulously sorted her files and deposited a vast archive of her work at the Gardens – a remarkable assemblage of books, specimens, museum items and other ephemera associated with the Irish flora. She remained intellectually agile and fascinated by all around her to her dying day. She will be greatly missed by her colleagues, the staff at the gardens and botanists both at home and abroad.