Irish Topographical Botany, or ITB as it is more familiarly known, was a landmark work in the history of Irish Botany.

About the ITB

For the first time a detailed geographical analysis of Ireland’s vascular flora was compiled. Most remarkable is that the work was spearheaded and largely undertaken by a single man – Robert Lloyd Praeger – in the space of just five years. As he states in the Preface to ITB:

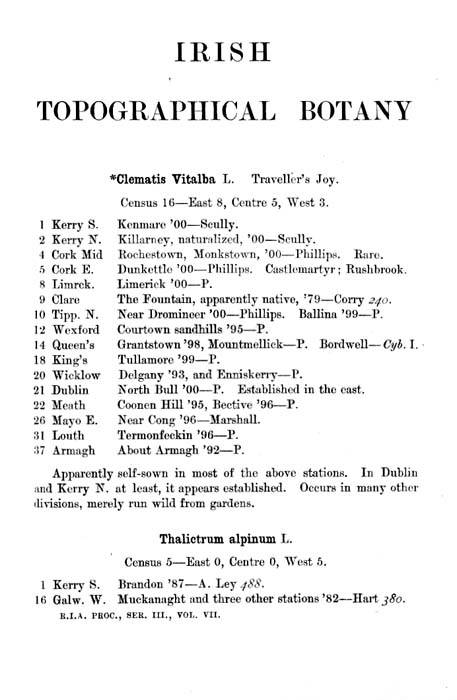

The need of an Irish “Topographical Botany” was forcibly brought to my mind in 1895, when perusing a copy of the ninth edition of the “London Catalogue of British Plants,” sent me by the editor, Mr. F. J. Hanbury, F.L.S, on noticing that Ireland was still necessarily excluded in the census-numbers appended to the species, owing to absence of detailed information concerning the distribution of plants in this island. In the “London Catalogue,” in fact, Ireland was placed on the same footing as the Channel Islands, its very existence being recognized only when a plant occurred in Ireland, but not in Great Britain. To assist in remedying this unsatisfactory state of affairs, if nothing more, I set about collecting information respecting the county-distribution of plants in Ireland.

Thus the aggregate records for the county-divisions, prefaced by the description of the divisions in the Introduction, may be said to form forty exceedingly condensed county Floras. This work may fairly be described as a companion to “Cybele Hibernica.” Its aim is to supply detailed information of such a kind, and in such a form, as lay outside the scope of that book. It was the publication of the second edition of “Cybele Hibernica” that made “Irish Topographical Botany” a possibility. In the absence of the immense amount of critical sifting, of sweeping away of errors, and settling of innumerable doubtful points, which the editors of “Cybele” accomplished, it would not have been possible to have produced the present work, at least single-handed, and in a period of five years. Furthermore, the publication of “Cybele” allowed the present work to be largely curtailed, and to include, so far as was consistent with its scheme and purpose, only additional matter; the reader being referred to “Cybele ” for information which it would have required further time to acquire, and further space to publish.

The long summer days spent in the Limestone Plain,

where the gentle undulations of the ground

only occasionally hid the distant rim of brown and blue hills;

the marshy meadows, heavy with the scent of flowers;

the great brown bogs, where the curlews alone relieved the loneliness;

the bare limestone pavements and gaunt grey hills of Clare and Galway;

the savage cliffs of the Mayo coast;

the flower-filled sand-dunes which fringe the Irish Sea;

the fertile undulations of southern Ulster;

the swift brown current of the Barrow;

the fretted limestone shores of the great western lakes;

the towering cones of the Galtees:

all have left memories that can never be effaced.Ireland is a delightful country for the pursuit of work in the field.

Enclosed or preserved ground is but seldom met with,

and the country is free and open.

Few rivers but can be, forded;

few marshes or bogs but can be crossed;

few precipices but yield their treasures to the mountaineer;

few spots are so remote but they may be visited

in a good day’s walking from the nearest stopping-place.

Surface.- The most noticeable surface-features of Ireland are a number of more or less detached mountain-groups formed chiefly of Palaeozoic rocks, of elevations varying from 1500 to a little over 3000 feet, disposed mainly around the coast, and a great central plain of slightly undulating Carboniferous limestone, raised only a couple of hundred feet above sea-level, and broken occasionally by low hill-ranges, formed generally by simple folding. Ireland is, for its size, the flattest island in the world. Lakes are numerous but irregularly distributed; the proportion of water to the whole area is no less than one to thirty-three. More remarkable is the great extent of surface which is covered by peat bogs. In spite of the continual cutting of turf for fuel, the proportion of low-level bog to the whole area is at the present time 1 to 17. In the province of Connaught one-eighth of the entire surface is officially returned as peat bog.

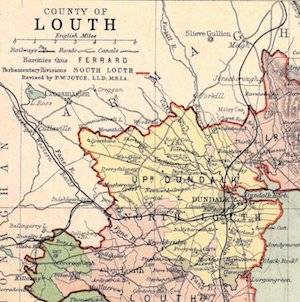

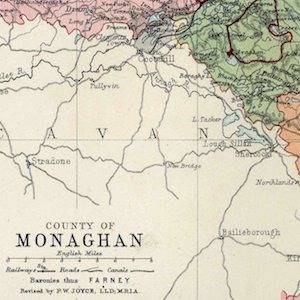

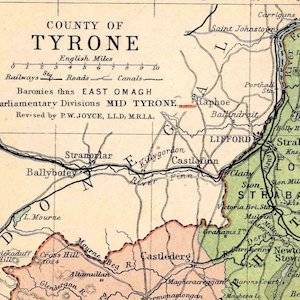

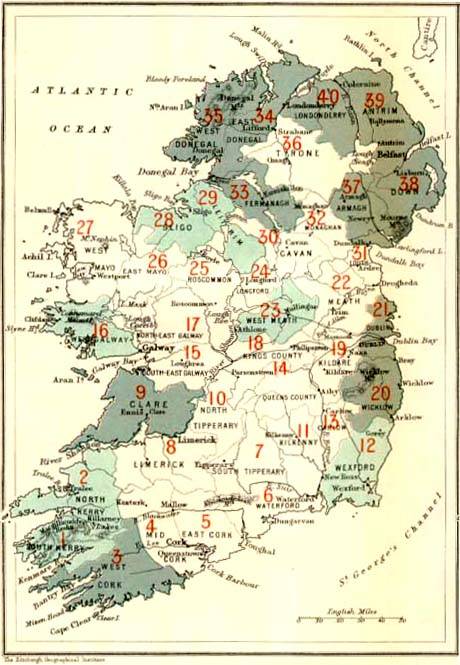

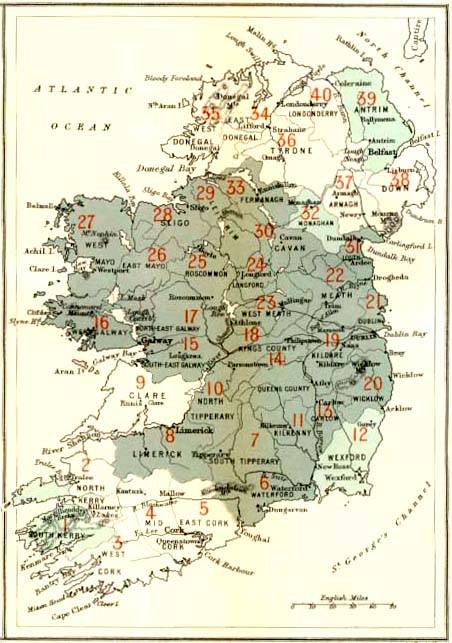

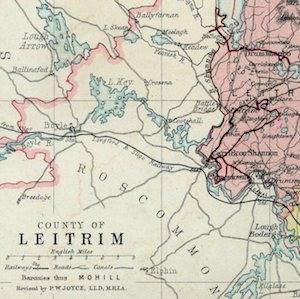

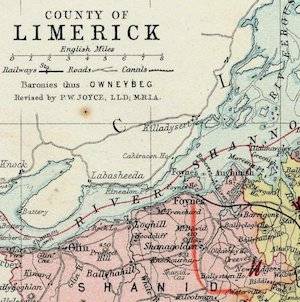

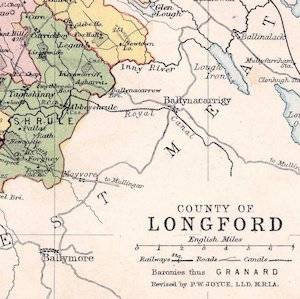

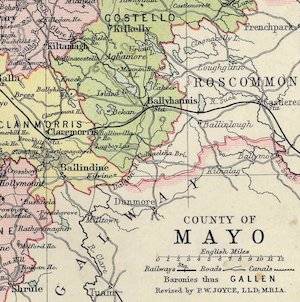

Praeger divided Ireland into 40 vice-counties.

These botanical divisions correspond in the main with the Irish counties. However, because it was desirable to have the unit of area to more or less correspond between each of these divisions, the six largest counties were sub-divided into 14 smaller divisions. Other considerations when drawing these boundaries were the presence of natural boundaries, the nature of the boundary, the equalization of areas and the practicality of these. Not all the vice-county boundaries therefore follow the administrative county boundaries. Since the publication of ITB, two further papers have clarified and defined these boundaries (D.A.Webb, 1980, The biological vice-counties of Ireland, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 80B (12) 179-196; D.L.Kelly, 1984, Irish Naturalists’ Journal, 21: 365). A Summary of each vice-county, both physical and botanical makes up much of the introduction to ITB.

Praeger next went on to describe, in some detail, the methods and practicalities of the field work:-

… in the present case the bulk of the compiler’s task lay in the creation of the necessary records by means of systematic field-work. As the field-work thus carried out constitutes the most extended botanical survey yet made in Ireland, some notes on the circumstances under which it was undertaken, and the means employed in its execution, may be of interest.

The state of knowledge as regards county-lists in 1895, when I projected “Irish Topographical Botany,” may be summarized as follows :

| A.- Flora well known (say, not less than 400 species) | ||

| DIVISION | CHIEF SOURCES OF INFORMATION. | |

| 3 Cork West | Allin’s Flora (1883). .. | |

| 9 Clare | Foot, Hart, Stewart, Corry , &c. | |

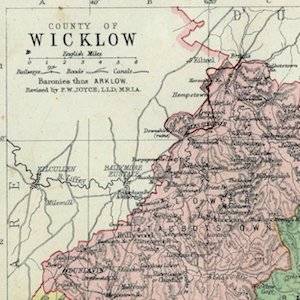

| 20 Wicklow | Brit. Assoc. Guide (1878). | |

| 21 Dublin | B.A. Guide (1878) ; Hart’s “Howth” and “Lambay.” | |

| 33 Fermanagh | Papers by Barrington & Vowen, and Stewart. | |

| 34 Donegal East | Hart’s Papers, and Flora (in press). | |

| 35 Donegal West | ||

| 37 Armagh | Praeger’s Flora (1893). | |

| 38 Down | Stewart & Corry’s Flora (1888) and Supplement to same (1895). | |

| 39 Antrim | ||

| 40 Derry | ||

| B. – Flora partially known (say, 200 to 400 species) | |

| 1 Kerry South | Papers by Hart, Barrington, Scully, &c. |

| 2 Kerry North | Hart, Stewart, Scully, &c. |

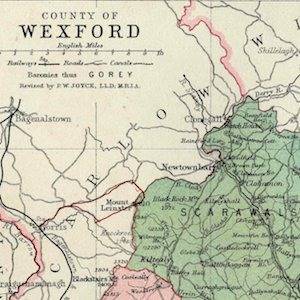

| 12 Wexford | Hart, Barrett-Hamilton & Moffat, &c. |

| 16 Galway West | Babington, More, Hart, &c. |

| 23 Westmeath | Barrington & Vowell, Levinge. |

| 28 Sligo | Corry, Barrington & Vowell. |

| 29 Leitrim | Stewart, Barrington & Vowell. |

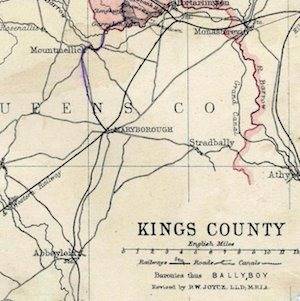

C. Of the remaining 22 divisions, 100 species per division would have been a high estimate of the average number of plant-records available. Of some of these divisions such as North-east Galway, King’s County (=Offaly), Meath, East Mayo, and Monaghan, the flora was almost totally unknown.

Again, the flora of an average Irish county-division might be reckoned at 600 to 700 species. Of these, say 100 would be rare or local species, few of which one could hope to meet in the course of a rough and hasty survey such as alone it would be possible to carry out, considering the many divisions to be explored, and the small number of workers. Thus 500 to 600 species per division was left as the available maximum to be aimed at, and I felt that publication might be undertaken if a minimum of 500 species per division could be shown ..

Out of 20,000 county-records required ( 500 species in 40 divisions), it appeared from the summary given above that about 8000 were available in 1895, leaving about 12,000 to be got together by means of field-work. In addition, it was desirable that many old records which were included in these 8000 should be replaced by others of recent date; so that 15,000 might be taken as the number of new records required to make the county-lists reasonably complete and up-to-date. Dr. Scully had been in recent years working out the distribution of plants in Kerry (divisions 1 and 2), Mr. Phillips in Cork (3, 4, and 5), and Mr. Colgan in Dublin (21), and from these six divisions there was therefore hope of obtaining full lists of recent date. For myself, I was willing to devote my holidays for five years to the work, which, taking 40 days per annum as the available total, would give 200 days field-work. Careful consideration showed that, with the assistance which I might hope to receive in other directions, there was reason to think that the end of five years might see the stipulated 500 species on record for each of the 40 divisions. The sequel has shown that these expectation were well founded. Only one county (Monaghan, 477 species) falls below the stipulated 500, and that on account of an accident; while the average number of plants recorded for the 40 divisions is 628.

. . . In all, I spent just the estimated 200 days in the field working up county-lists for use in the present compilation. The conditions which governed the distribution of this field-work were somewhat complicated. First, an estimate, in 1895 of the state of advancement of all the county- lists, reckoning both all work then in existence and work likely to be done by others, gave me the relative number of days that ought to be devoted to exploring each division. Then the total number of days which I could hope to devote to the work during the five years had to be distributed among the divisions in these proportions. The number of days to be spent in each division being thus determined, attention had again to be directed to the work already done, and a note made of the portions of each division already worked, so that unexplored regions should have preference. Then care had to be taken in planning expeditions that every kind of ground should be worked, so that mountain and stream, bog, marsh, sea-shore, lake, wood, esker-ridge, should all yield their quota to the flora; and the dates of visits had to be planned so that the plants neither of early spring, of summer, nor of autumn, should escape notice. Lastly came the dove-tailing of the various expeditions, so that the above conditions should be fulfilled without any unnecessary time being spent in travelling. Fortunately, the most remote parts of the country – Cork and Kerry, Donegal, Derry and Antrim, were to be reckoned among those the flora of which had previously been worked out, or was already in capable hands. Still the area to be explored was sufficiently extensive, stretching from Wexford and Louth westward to Connemara and Sligo, and from Waterford and South Tipperary northward to Fermanagh. The portions of the country which had been previously examined were naturally the more interesting districts – the extreme South-west, Burren, Connemara, the Ben Bulben district, Donegal, Antrim, Dublin, and Wicklow: also the principal mountain-groups, lakes, and rivers – in fact, almost all the places to which the botanist would naturally turn his steps. Likewise, it was the rarer and more interesting species to which attention had chiefly been directed. In consequence, much of my work lay in the little-known Central Plain, and among plants which do not possess the fascination that pertains to the Cantabrian group or to the alpine flora; In some ways this restriction was beneficial, as it led to the exploration of many districts which might have long remained unvisited by the botanist, and to the finding of a number of interesting plants which otherwise might for years to come have escaped detection. My field-work, indeed, proved exceedingly interesting, and it has left behind the pleasantest of recollections. The long summer days spent in the Limestone Plain, where the gentle undulations of the ground only occasionally hid the distant rim of brown and blue hills; the marshy meadows, heavy with the scent of flowers; the great brown bogs, where the curlews alone relieved the loneliness; the bare limestone pavements and gaunt grey hills of Clare and Galway ; the savage cliffs of the Mayo coast ; the flower-filled sand-dunes which fringe the Irish Sea; the fertile undulations of southern Ulster; the swift brown current of the Barrow; the fretted limestone shores of the great western lakes; the towering cones of the Galtees: all have left memories that can never be effaced.

Any account of the botanical excursions of the last five years would be out of place here, but brief narratives of the field-work of 1897, 1898, 1899, and 1900 will be found in the pages of the ” Irish Naturalist.” Ireland is a delightful country for the pursuit of work in the field. Enclosed or preserved ground is but seldom met with, and the country is free and open. Few rivers but can be, forded; few marshes or bogs but can be crossed; few precipices but yield their treasures to the mountaineer; few spots are so remote but they may be visited in a good day’s walking from the nearest stopping-place.

Praeger’s field-methods and the data he acquired during his expeditions is preserved in the Library of the National Botanic Gardens.

An example, showing the manuscripts associated with Prager’s London Catalogue for county Cavan is given below.

As regards methods employed in the field-work, there is little to be said. With a large vasculum, a “London Catalogue,” and the one- inch hill-shaded Ordnance Survey map as my constant companions, progress was smooth and rapid. In marking the catalogues, letters were used to signify not only localities, but the dates on which the localities were visited. Thus, if a place was visited twice, a different letter would be used on the second occasion; and the particulars relating to any plant could thus at any future time be determined by means of a key-list of letters and their equivalents at the beginning of the catalogue. A separate catalogue was used for each division. So far as possible, specimens were dried of all plants that could not be named in the field; but on account of the number of plants collected, and the amount of ground covered, it was soon found impossible to collect Rubi and other bulky specimens. The Willows suffered from the same cause, and on account of the impossibility of revisiting places at different times of year. My hasty surveys were likewise insufficient for the working out of the distribution of critical forms: our knowledge of such plants can only be acquired by slow and patient observation. In certain groups, however, notably Characeae, large collections were made, which have much extended our knowledge of their range in the Country.

In the case of each division, it was found advantageous, when about three days’ work had been carried out, to form, from the marked catalogue, a desiderata-list of all common plants not yet seen, and to keep this list prominently in view; otherwise there was a danger that even conspicuous plants of universal occurrence might escape being noted. The number of days devoted to each division was, as has been already stated, determined by the amount of work done in each by previous observers, and the first four years’ work was carried out according to this estimate. At the end of the fourth year, a table of distribution was constructed for the whole flora in the forty divisions, including both my own and previous work. From this table desiderata-lists were formed for each division, of all yet unrecorded plants likely to occur in each, and the last season’s work was distributed among the divisions in proportion to the length of these lists.

In estimating the time devoted to each division, six hours or more in the field was reckoned as a ” day”; less than six hours as a half-day. The ordinary “day,” however, consisted of twelve hours – 8.30 a.m. to 8.30 p.m. – and the walking distance covered per day averaged 20 to 25 miles, with a minimum of about 15, and a maximum of 35. Anything over a 25-mile day, however, generally meant a steady tramp as the beginning or end of the day’s work.

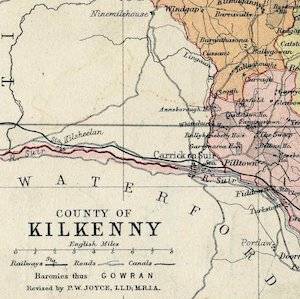

The rate of growth of the county lists is a rather interesting point. Two typical cases from my catalogues may be quoted; Kilkenny and Carlow may be taken as average inland counties (The flora of an average maritime division is larger by 40 to 50 species than that of an inland division):-

| 11 KILKENNY | ||

| First day, May 19, 1897. | About Kilkenny | 244 species |

| Second, July 30, 1898. | Thomastown | 135 |

| Third, July 31, 1898. | L. Cullin and R. Suir | 70 |

| Fourth, Aug. 1, 1898. | Inistioge and Graigue | 37 |

| Fifth, Aug. 2, 1898. | Urlingford | 22 |

| Total for 5 days work | 508 species | |

| 13 CARLOW | ||

| First day, May 18,1897 | Bagenalstown | 251 species |

| Second, Aug. 9, 1898 | Carlow and Milford | 133 |

| Third, Aug 10, “ | Borris and Mt.Leinster | 48 |

| Fourth, Aug 11, “ | St.Mullin’sand Graigue | 29 |

| Fifth, June 4, 1899 | Tullow | 27 |

| Total for 5 days work | 488 species | |

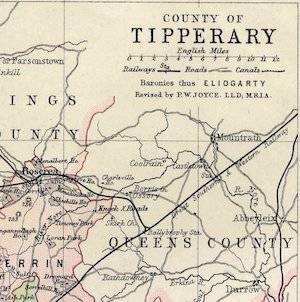

The largest number of species noted in a single day’s work in any of the inland counties was between 370 and 380; this figure was reached in North Tipperary within a 5-mile radius west and south of Portumna, and again in Westmeath, within 5 miles north and east of Athlone. In each case there was a varied combination of river and lake, bog and marsh, but no maritime or mountain plants. One day spent in the Carlingford district, where there is a delightful variety of sea-shore, mountain, and fertile ground, yielded a list of over 400 species.

It only remains to add that a large amount of detailed notes, referring to the greater number of the divisions, is left unpublished. The “word frequent,” so often appended to my own records, signifies a number of further records, localized ,and dated; and indirectly often some scores of miles of country explored. The material on which the records of most of the rare or critical species are based will be found in the National Museum (the National Herbarium is now at the National Botanic Gardens), to the extent of some 5000 sheets of specimens, the critical plants named by recognised authorities; the bulk of the notes remains in my own hands, and is at the disposal of any fellow-botanist engaged in working up the flora of any district or the distribution of any group of plants.

Praeger’s Manuscript Material for Irish Topographical Botany at the National Botanic Gardens

When compiling data for Irish Topographical Botany, Praeger noted his field-records for the 22 poorly-known vice-county in separate copies of The London Catalogue of British plants (9th edition). These catalogues are preserved in the Library at the National Botanic Gardens, where they provide a valuable data source for present-day botanists.

Praeger described the methodology of his field work thus:

With a large vasculum, a “London Catalogue,” and the one- inch hill-shaded Ordnance Survey map as my constant companions, progress was smooth and rapid. … A separate catalogue was used for each division.

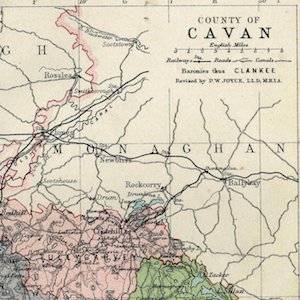

The cover of the Cavan catalogue (it is vice-county number 30) is shown below.

So far as possible, specimens were dried of all plants that could not be named in the field.

These specimens are preserved in the National Herbarium at the National Botanic Gardens.

In marking the catalogues, letters were used to signify not only localities, but the dates on which the localities were visited. Thus, if a place was visited twice, a different letter would be used on the second occasion; and the particulars relating to any plant could thus at any future time be determined by means of a key-list of letters and their equivalents at the beginning of the catalogue.

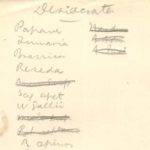

The list on the inside cover of the Cavan catalogue is shown below.

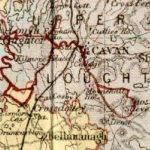

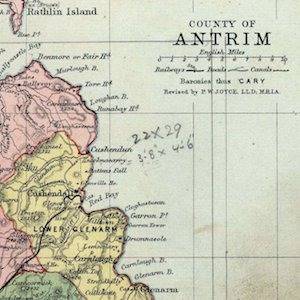

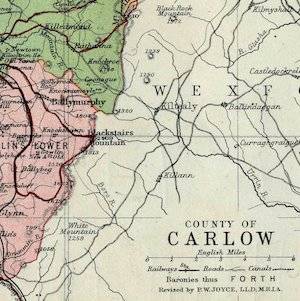

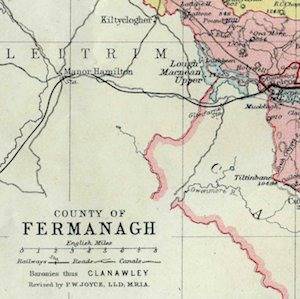

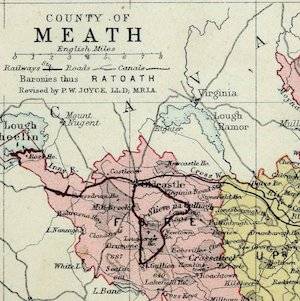

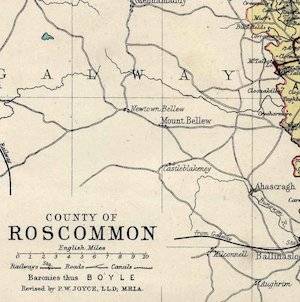

In addition, Praeger also incorporated a map of each county from Philips’ Handy Atlas. On these individual maps of each county, he marked the routes he followed in red ink. These provide an important record of the exact route that Praeger followed in each county during his work towards ITB. The complete itineraries, with detailed maps of each route followed, is available below.

The routes, as marked by Praeger, for his excursions around Cavan town on the 17th-18th May, and 10th-13th July 1896 are shown below. These routes provide details of Praeger’s field work that is recorded no where else. He did not usually give detailed localities on his herbarium specimens, so that the itineraries and routes provide an invaluable record for localising his herbarium records more fully.

In the case of each division, it was found advantageous, when about three days’ work had been carried out, to form, from the marked catalogue, a desiderata-list of all common plants not yet seen, and to keep this list prominently in view; otherwise there was a danger that even conspicuous plants of universal occurrence might escape being noted.

The ‘desiderata’ list for Co. Cavan is shown below.

At the end of the fourth year, a table of distribution was constructed for the whole flora in the forty divisions, including both my own and previous work. From this table desiderata-lists were formed for each division, of all yet unrecorded plants likely to occur in each, and the last season’s work was distributed among the divisions in proportion to the length of these lists.

The list for Co. Cavan covers two pages of foolscap, and only a part is shown below.

- The cover of the Cavan catalogue (it is vice-county number 30).

- The list on the inside cover of the Cavan catalogue.

- The routes, as marked by Praeger, for his excursions around Cavan town on the 17th-18th May, and 10th-13th July 1896.

- The ‘desiderata’ list for Co. Cavan.

- The list for Co. Cavan covers 2 pages of foolscap, and only a part is shown.

Praeger’s Itineraries and Maps

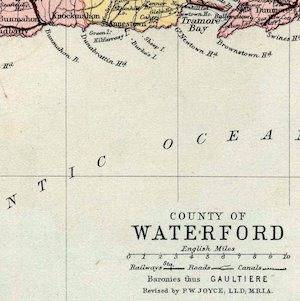

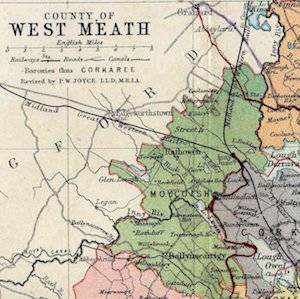

In preparing Irish Topographical Botany, Robert Lloyd Praeger conducted some 200 days of fieldwork from 1896 to 1900 in 29 of the 40 vice-counties (asterisked below). For each vice county he annotated a copy of the ninth edition of the London Catalogue of British Plants. Each visit to the county was coded with a letter, and an index to these visits, and their dates was given at the front of the Catalogue. The routes were also marked on a map from the Philips’ Handy Atlas of the Counties of Ireland.

Praeger’s methodology for the collecting of information is described. The London Catalogues are kept at the National Botanic Gardens, and the information below has been collated by Rosemary Goode.

In the accompanying files, where itineraries and maps are available they are given. Praeger did not conduct the same methodical fieldwork in all Irish counties, and his itineraries only cover those vice-counties asterisked (*) below. For a number of vice-counties the maps are missing (†), and in these and other cases, unmarked Philips maps are provided, since these supply valuable locality information used by field workers at the turn of the century.

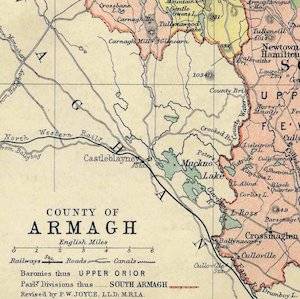

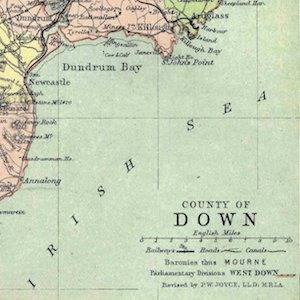

Armagh H37

Download a high resolution map here.

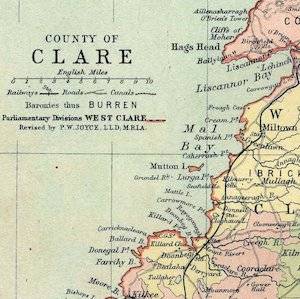

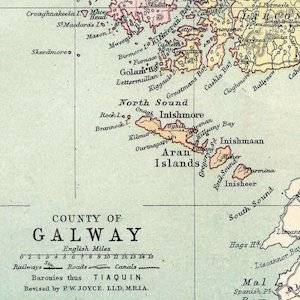

Clare and the Aran Islands H9

Download a high resolution map here.

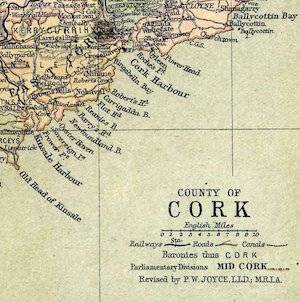

Cork West H3, Mid H4, East H5

Download a high resolution map here.

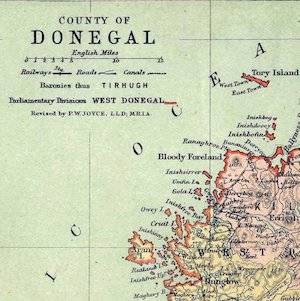

Donegal East H34, West H35

Download a high resolution map here.

Down H38

Download a high resolution map here.

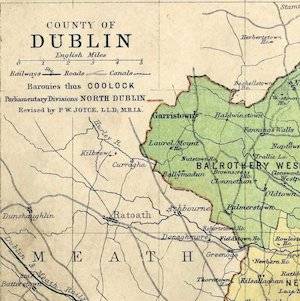

Dublin H21

Download a high resolution map here.

Galway South East H15*, West H16*, North East H17*

Download a high resolution map for Galway South East, Galway West, and Galway North East.

Download the itinerary here.

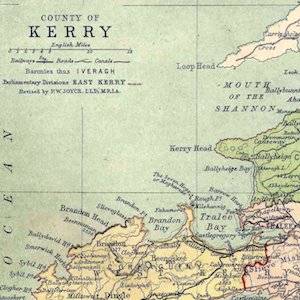

Kerry South H1, North H2

Download a high resolution map here.

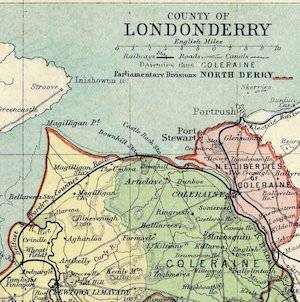

Londonderry H40

Download a high resolution map here.