Author: Noeleen Smyth, Edel McDonald (OPW) & Tony Murray (NPWS)

Date: 21st September 2018

During the super-hot summer of 2018 we enjoyed Mediterranean weather. Many of us went to the sea to enjoy the heat and unusual sunshine, which on a dreary September day seems like a long time ago. The hot summer put us at the National Botanic Gardens in mind of an autumnal expedition to see how one of our rarest Irish coastal plants fared, the very exotic and Mediterranean Achillea maritima also known as Otanthus maritimus or Cottonweed.

We discovered that shockingly just 12 individuals are left in the one remaining Irish site in Co. Wexford. In the past, it was also been recorded in three other Irish counties: Wicklow, Waterford and Kerry. The last known record for Wicklow was 1964, Waterford 1883 and for Kerry it has been over 262 years since the last record at Ballyheige in 1756. Our Nursery manager Edel McDonald has kept a very watchful eye on this plant in our collections and carefully grown this species at Glasnevin for many years.

Cottonweed (Achillea maritima also formerly known as Otanthus maritimus) in Irish “Cluasach mhara” is a small shrubby perennial, which grows around 25 cm tall, it has very attractive silver foliage in a shiny silvery pelt of “felty” foliage. The flowers are small 8mm across and tubular yellow packed into a flower head described by Wildflowers of Ireland author Zoë Devlin as “button-like, so a furry plant with yellow button flowers as well as being rare it is a very attractive ornamental plant.

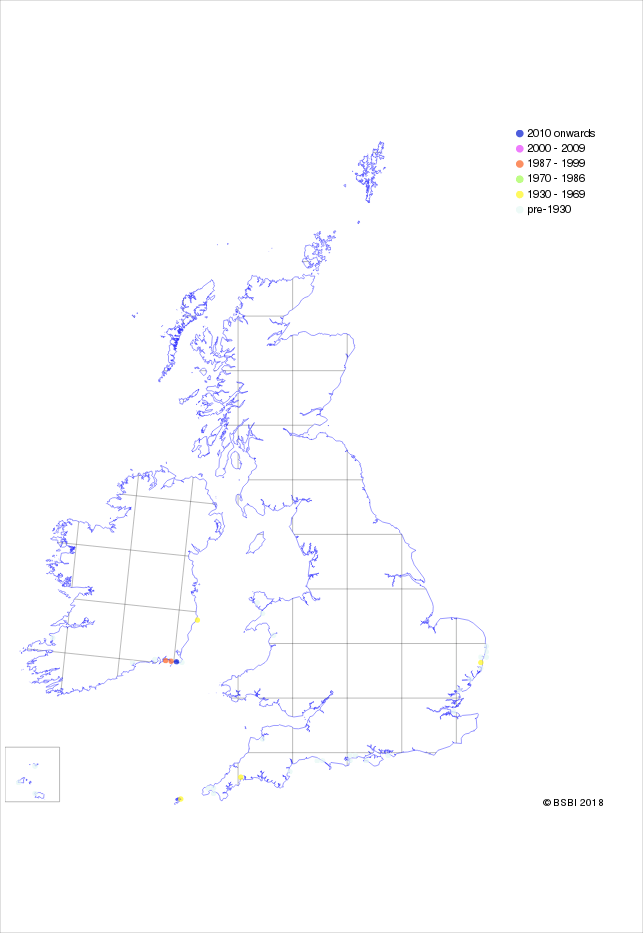

You would have to travel to the west coast of France or the Iberian Peninsula to next encounter this Irish species. It is extinct in Britain, the last records being from Cornwall in 1933 and the Isles of Scilly in 1936 and the Channel Islands (on Jersey) in 1926. According to the online atlas of the British and Irish flora this species has undergone a major decline in Ireland since 1850 and it is now restricted as a native to just one site in Co. Wexford.

Cottonweed is a species of coastal sand dunes, strandlines and gravel banks, where it occurs in open areas on coarse, sandy gravels, it does not thrive on fine-grained sandy sediments, which favour the growth of Marram (Ammophila arenaria), a species that outcompetes Cottonweed. The remaining plants of Cottonweed occur in a vegetation community that includes common coastal species such as Rock samphire (Crithimum maritimum), Sea holly (Eryngium maritimum), Sea sandwort (Honkenya peploides) and Autumn hawkbit (Leontododon autumnalis = Scorzoneroides autumnalis). Sea Cottonweed is a protected Irish species under the Flora Protection Order 2015 and now classified as ‘CRITICALLY ENDANGERED’ in the new Red List of Irish Vascular Plants 2016.

Edel McDonald NBG & Tony Murray NPWS with the few remaining Cottonweeds in Ireland in Co. Wexford. Note the flowering yellow autumn hawkbit (Leontododon autumnalis = Scorzoneroides autumnalis). (Photo N. Smyth).

Cottonweed is specially adapted to its coastal environment

Preston & Hill described Cottonweed’s niche in Ireland as “precarious”, in their formative work on the geographical relationships of British and Irish vascular plants in 1997, as in Europe it tends to frequent more “stable” Mediterranean beaches, much like ourselves during our summer exodus to Mediterranean beach resorts.

Coastal and dune plants also known as “psammophytes”, a lovely word derived from Ancient Greek, which means, “sand loving”. Many coastal plants decide to live and adapt to the stresses of growing in a dynamic coastal environment. The stresses include salt spray, low nutrient and water availability, substrate instability and sandblasting. We all know it’s not too pleasant at the beach on a windy day, trying to get our towel down and realising we left the sun cream, lunch and water bottle in the car.

Cottonweed has the ability to survive these extremes with its pubescent or “furry” exterior, found on both sides of the leaf, which helps to reduce water loss and helps keep the plant cool. Its stomata (tiny pore openings in plants used for gas exchange, usually found on the undersides of leaves) are, along with many other “psammophyes”, found on both sides of its leaf, which can help the plant to breathe if one surface is covered in sand. Many coastal plants can also roll their leaves up to stop gas exchange during periods of extreme drought and Cottonweed is no different, it too can roll its leaves up tightly to bury and protect its stomatal openings creating what is known as “stomatal crypt” (Daniela et al. 2009).

One reason often cited as a reason to protect our rare plants is that they may house some valuable disease fighting chemicals. So if being rare, lovely, furry and silver with yellow buttons is not enough reason for you to love Cottonweed as we do, a recent Portuguese study found that that the chemicals in the essential oils are known for their microbial activity and also demonstrated the ability to destroy certain cancer cell lines (Poças 2014).

Conservation outlook for Irish Cottonweed

We have been growing Cottonweed at the National Botanic Gardens for a number of years. Our nursery manager Edel McDonald has the special “grey” fingers required for growing this plant; we currently have five mature plants and dozens of newly rooted and rooting cuttings. We grow these as an insurance policy just in case anything happens to the very precious remaining twelve plants at the one site in Co. Wexford. This work also helps to fulfils one of the aims of the botanic gardens and the National Biodiversity Action Plan i.e. to develop ex situ conservation programmes for our rarest plant species outlined in Target 6.3 (NBAP 2017).

Last week we paid the Cottonweed site in Wexford a visit to see how the remaining twelve wild plants are faring and, under licence and in the company of NPWS staff, we collected more seed and cuttings and planted three plants with the hope to add even more to the population with plants grown by Edel at Glasnevin.

As this is, a Mediterranean species is at the edge of its range here in Ireland some of our predicted future climate change scenarios where we heat up could help to increase the range for the species. However, with more stormy conditions and a sea level rise of 0.5m predicted by the end of the century this could certainly spell the end for this iconic Irish coastal species. In the meantime. Whatever the future holds in order to assist the future survival of this fascinating and beautiful member of the Irish flora, it is important that a sizeable back-up population propagated from wild Irish plants is developed and grown ex –situ here at the gardens. We look forward to continuing to play our part where we will be helping to help bulk up the numbers to conserve a very rare iconic coastal species.

Cottonweed (Achillea maritima = Otanthus maritimus) growing at the National Botanic Gardens (Image: N. Smyth)

Map showing the distribution of Cottonweed in Britain and Ireland- note that it now extinct in the UK and only one site (dark blue dot) remains in Ireland. (Image: BSBI)

Edel McDonald tending to precious Irish Cottonweed plants at the National Botanic Gardens (Image: N. Smyth)

References and Further reading

Poças J, Lemos MF, Cabral C, Salgueiro L and Pires IM (2014). Assessment of Anticancer Properties of Essential Oils from sand dunes of Peniche (Portugal). Front. Mar. Sci. Conference Abstract: IMMR | International Meeting on Marine Research 2014. doi: 10.3389/conf.fmars.2014.02.

Carter, R. W. G., et al. “The Ecology and Present Status of Otanthus maritimus on the Gravel Barrier at Lady’s Island, Co Wexford.” The Irish Naturalists’ Journal, vol. 20, no. 8, 1981, pp. 329–331. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25538540.

Daniela, C. , Costantina Forino, L.M., Balestri, M. & Pagni, A.M (2009) Leaf anatomical adaptations of Calystegia soldanella, Euphorbia paralias and Otanthus maritimus to the ecological conditions of coastal sand dune systems, Caryologia, 62:2, 142-151.

Flora Protection Order 2015. http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2015/si/356/made/en/print

NBAP 2017. National Biodiversity Action Plan 2017 -2021. Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. https://www.npws.ie/sites/default/files/publications/pdf/National%20Biodiversity%20Action%20Plan%20English.pdf

NPWS 2013. Special Area of Conservation 000671. Tramore Dunes and Backstrand. https://www.npws.ie/sites/default/files/protected-sites/synopsis/SY000671.pdf

Preston, C.D. & Hill, M.O. 1997. The geographical relationships of British and Irish Vascular Plants. The Botanical Journal of the Linnaean Society. Vol. 124, Issue 1, pp. 1–120 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.1997.tb01785.x

Wildflowers of Ireland p131 http://www.wildflowersofireland.net/plant_detail.php?id_flower=72