Carl Linnaeus, the man who named the human race – Homo sapiens – was born three hundred years ago on the 23rd May 1707. Strangely his family name derives from a Lime tree (Linden) growing on his father’s land – quite literally the name means Lime-man. At the time the use of patronyms was losing favour in Europe, and his father had been obliged to compose a family name when entering the University of Lund.

Here was a man who never lost his wonder of creation, and who, in his own reckoning, was on a mission from God. He summed up his life’s work in one of his four autobiographies! as “God Created, Linnaeus ordered”. In every way he was egoistic beyond belief, but we have to acknowledge that he was probably justified in this presumption. He quite literally completed the task begun by Adam of naming “all the creatures the Lord God formed, every beast of the field, and every fowl of the air”.

More remarkable still, Linnaeus achieved notoriety at the tender age of 25, when he proposed a radical new way of identifying and classifying plants, animals and minerals. At the time scarcely 8,000 species of plant were known, but Linnaeus set about methodically cataloguing these, and collecting all the names being used in different European states. He produced an encyclopaedic reference book to them all, and christened each with a binomial name. These scientific names are still in use to this day, and were one of his greatest innovations. Unlike our names, consisting of forename and family name, these scientific names give the general first and the specific second. Thus the domestic horse is Equus caballus while the common plains’ zebra is Equus quagga.

A sketch by Linnaeus of Andromeda polifolia with a newt (right) and the maiden Andromeda awaiting recue by Perseus from the sea-dragon (left). He was not a great artist, as the picture he did in his Lapland diaries to illustrate a small pink-flowered shrub in the Heather family – Andromeda polifolia – shows. He established the new genus based upon the far-fetched allegory of Ovid’s tale of Andromeda chained to the rocks as a sacrifice to the sea dragon (a newt!).

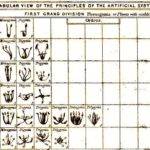

Linnaeus was a highly pragmatic worker and believed in the democratisation of science. He therefore expounded a truly startling method of identifying plants which gave his detractors much ammunition. This was his sexual system, which merely required the observer to count the number of anthers (the male parts of the flower) and ovaries (the female parts). To him the flower was “the bridal bed which the creator has so gloriously prepared, adorned with such precious bed-curtains and perfumed with so many sweet scents in order that the bridegroom and bride may celebrate their nuptials with the greater solemnity.”

Thus an Iris has three anthers and one ovary, and in Linnaeus’ words was like three husbands in the same marriage. Whilst the poppy and lime tree enjoyed the state of ‘twenty males or more in the same bed with the female”. The marigold flower on the other hand comprised ‘many marriages, in which the married females are barren and the concubines fertile’. Such imagery, not surprisingly, was regarded with horror by the strait-laced. But it gained European wide popularity and persisted for 50 years after his death as a simple and readily learnt method for identifying plant species (see below). Whilst we may no longer use his method of cataloguing, his method of naming all living things is followed to this day.